The current health of the uranium market required bold and unprecedented steps by the industry to put supply and demand back into equilibrium. In 2018 the world’s #2 producer, Canada-based Cameco Corp (NYSE: CCJ), put its massive McArthur River mine on “Care & Maintenance”. McArthur River was producing 18M lbs/year and has a nameplate production capacity of 25M lbs/year. Not only were those pounds removed from the market, but because Cameco had a forward contract book they had to continue to deliver into, it has required Cameco to purchase over 56M lbs in the open market over the last four years. That means that the cumulative “swing factor” that arose from Cameco’s McArthur shutdown decision has exceeded 100M lbs.

Cameco was not the only large producer that has exercised discipline. Former 100% SOE – and the world’s largest producer, Kazatomprom (LSE: KAP), since floating 25% of its equity to private investors in 2018 – has demonstrated western-style business thinking of prioritizing “value over volume” (i.e. a focus on profits as opposed to production volumes). In 2018, Kazatomprom cut its production to 20% below the “Subsoil Use Agreement” targets and has committed to maintaining those reduced production levels through the end of calendar 2023. Kazatomprom’s production cuts have prevented a further 100M lbs from hitting the market. Over the last 21 months, another supply constraint emerged as COVID-19 work stoppages and interruptions further tightened an already-tightening market.

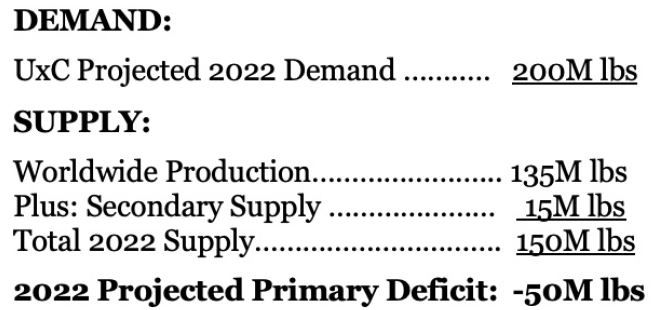

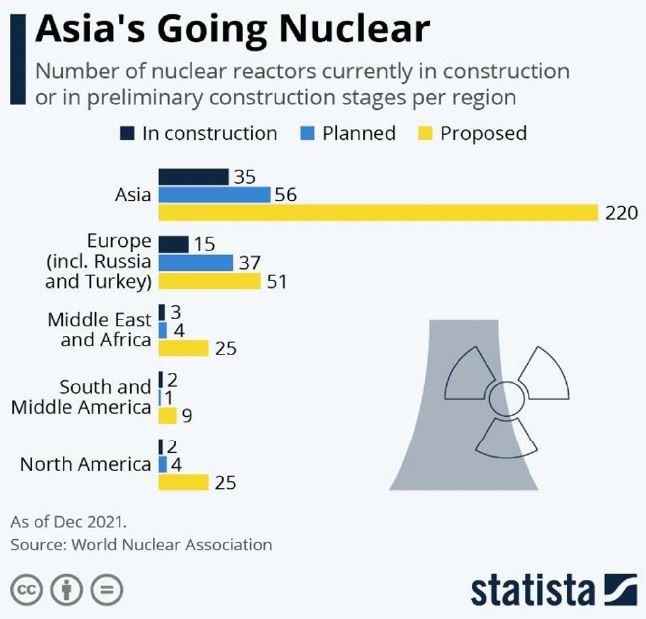

Leading nuclear industry consultancy firm, UxC Consulting, has just issued their projection for primary uranium supply and demand for 2022. The numbers are stark. UxC is projecting primary production of 135M lbs vs worldwide demand of 200M lbs…but that demand does not include the “financial demand” outlined in the article “Securitization Takes On a ‘Pivotal Role’” (see p.12). Let’s take a snapshot look at these numbers to get a truer “global” picture:

We have employed a very conservative estimate of “financial demand” for 2022 (e.g. we assume that the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (SPUT) will acquire pounds at only 1/3 the pace in ’22 as compared to ’21, despite the fact that we expect an NYSE listing by mid-2022). Based upon this conservative analysis, the 2022 structural deficit expands from -50M lbs to -87M lbs. We wish to point out that Uranium Insider is completely ignoring any repeat of the purchase of over 10M lbs of uranium by pre-production companies that occurred in calendar year 2021.

Unlike other industries or commodity sectors, there has been essentially no immediate supply response to the supply/demand situation that is now clearly out of balance. Why is that? Uranium mines take years to come online. For example, if a recommissioning decision of Cameco’s McArthur River occurred today it would take 18 months to fully get back online. Cameco has emphatically stated that McArthur River won’t be put back into production until those pounds have a “home” – meaning they are sold into long-term contracts with utilities.

Even when one takes into consideration future production coming online from:

- Cameco’s McArthur River (~18M lbs/year)

- KAP’s Budenovskoye in Kazakhstan (projected production: 6M+ lbs/year – which anecdotally KAP has stated is already fully contracted out through to 2027)

- Paladin’s Langer-Heinrich (“L-H”) project in Namibia (projected production 6M lbs/year – China National Nuclear Corp. owns 25% of Paladin and has a substantial “offtake” of future production)

- Orano’s Zoovch Ovoo deposit located in Mongolia (projected production; 3M+ lbs/year)

- enCore’s Texas-based Rosita operation (projected production; 1M+ lbs/year)

- Boss Resources’ Honeymoon Project in Australia (projected production; 2.5M+ lbs/year)

- Global Atomic’s Dasa Project in Niger (projected production; 4M+ lbs/year)

- Vimy’s Mulga Rock Project located in Australia (projected production; 3.5M+ lbs/year)

- Production increases in Uzbekistan (~2-4M+ lbs/year)

- Increased production of 1M lbs/year from both Argentinian domestics and Ukrainian restarts

…we still project annual demand to be in excess of annual supply.

It is important to point out that the last bull run in this sector (2004-2010) occurred during a period where annual supply exceeded annual demand. The point we are making is that at some juncture, “security of supply” will become paramount for utilities around the world for this product which has no substitute.

To the bears that argue that Kazatomprom could quickly ramp production by 10-15M lbs/year, we respond that “even if they could, they won’t, and the company has already stated so”. Sidestepping the argument about whether FKAP in fact could easily ramp-up production, KAP’s management has been outspoken about their perception of the coming supply crunch. COO Askar Batyrbayev is already on record as saying there simply won’t be enough uranium, and it is clear to us they understand that they are going to be able to harvest from a much higher pricing environment in the years ahead.

While on the subject of Kazatomprom…shortly into the new year, violent protests broke out across many cities in Kazakhstan. The protests were initially incited by dramatically higher fuel prices. However, after several days of violence and property destruction it was clear that citizens’ grievances were much broader. In response, Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev sacked his entire cabinet and imposed a state of emergency across several Kazakh cities. As the protests continued, authorities resorted to more drastic measures such as shutting off internet connectivity and having the Central Bank of Kazakhstan suspend all normal banking activities for a period of time. While Kazakhstan has experienced social unrest in the past, the country-wide outbreak that occurred in the first week of January is unlike anything we’ve seen before.

The importance of highlighting the recent instability in Kazakhstan is because Kazatomprom as the world’s largest uranium producer produces ~46% of the annual global mine supply. While we believe with the military assistance received from Russia along with other former Soviet republics, order will be restored, uranium supply out of Kazakhstan was already expected to be under pressure in 2022, as the company had previously flagged ongoing supply chain issues related to COVID-19. The recent unrest in Kazakhstan, in Uranium Insider’s view, serves as a palpable reminder of how concentrated uranium supply is and equally how important security of supply is. We expect utilities to be paying very close attention to events in Kazakhstan while carefully considering long-term contracts with producers in safer jurisdictions.

How pressing is the need for new mines to come online? Look at the chart above created by industry consultant, TradeTech. Furthermore, you need to understand that this chart was created before China’s November pronouncement of their planned 150 nuclear plant buildout by 2035 and does not include any projected future demand from Small Modular Reactors (SMRs).

Even if one accounts for these new mines that are expected to come online and on time over the next several years – which is a rarity in mining – one must be knowledgeable about the uranium “fuel cycle” to understand when the end consumers will be able to secure new inventory. The length constraints of this piece do not allow for an elaborate discussion of the uranium fuel cycle, but succinctly stated, once yellowcake is put in a drum it then must go through a three-stage process that involves conversion, enrichment, and fuel fabrication. This process consumes approximately a twelve to eighteen-month timeline until that nuclear power plant receives those custom fabricated fuel rods for their reactor.

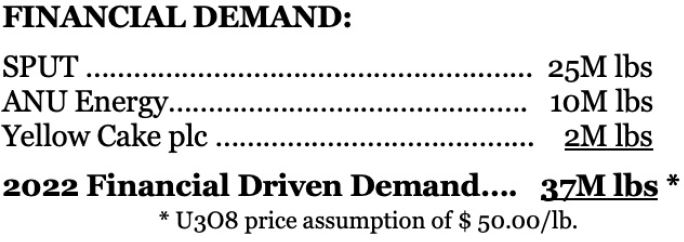

Put simply, supply cannot be brought on quickly and there has been no supply response whatsoever. In fact, quite the opposite has occurred with the arrival of SPUT in 2021. SPUT has continued to gobble up and sequester over 24M lbs of U3O8 and has raised in-excess of US$1.1B of new investor capital over the last 5 ½ months by virtue of their “At-the-Market” financing model…thereby further reducing future supply. To understand why we believe that we are on the verge of the largest long-term contracting cycle the sector has ever seen, examine the evidence in the chart overleaf, courtesy of Yellow Cake plc (AIM: YCA) (see profile on p.66). Because of the length of the fuel cycle, it won’t be long before both U.S. and European utilities will be addressing their uncovered requirements while at the same time competing with China for “security of supply”.

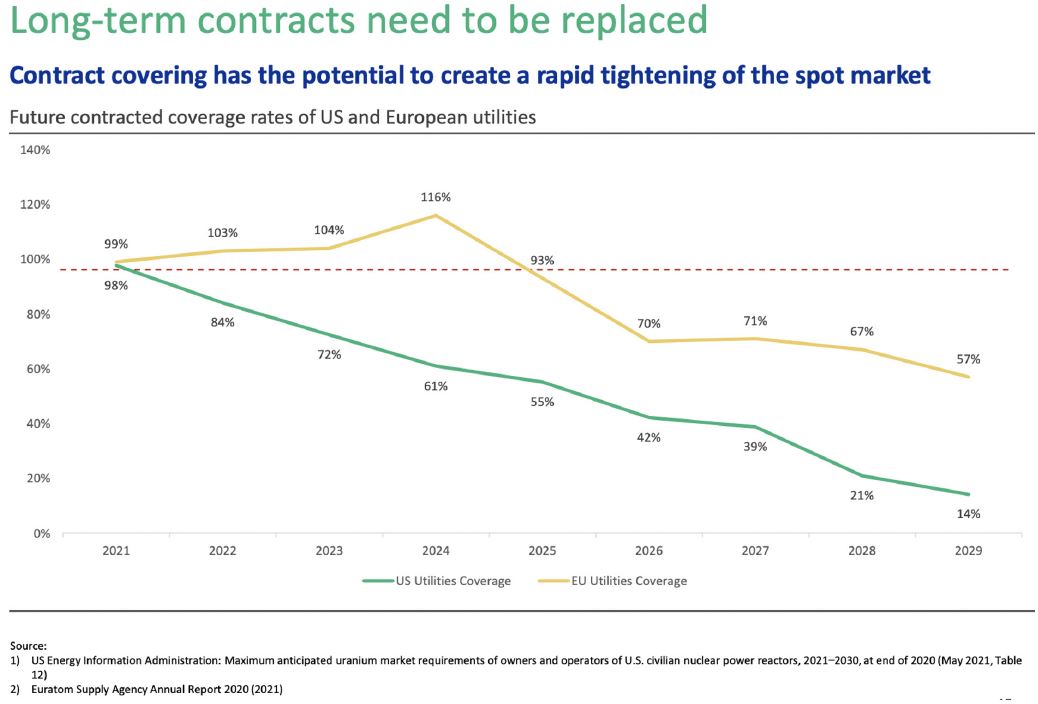

The world presently has 445 operating reactors and 57 under construction. Of the 57 new reactors under construction, 35 are being built in Asia, 15 in Europe, three in the Middle East, and four in the Americas. There are another 332 reactors that are planned and proposed. Within the last 60 days, China has announced its intention to put 150 new reactors in service by 2035 to reach their stated goal of 200GW of nuclear generation (China currently has ~51GW). To put that into perspective, that is more new reactors in the next 13 years than the entire world has built in the last 35 years. As you can see from the graphic on the right, Asia has been and continues to be the “growth driver”.

Another often overlooked factor is that many planned nuclear power plant retirements that analysts had pencilled into multi-year supply/demand models are not panning out as expected. This is due to both a growing recognition of nuclear plants having far longer useful lives, as well as recently legislated U.S. government financial subsidies now available to preserve these non-carbon-emitting power sources from planned retirement.

As previously stated, none of these industry projections are factoring in the impact that SMRs are expected to have on demand, and it could be quite significant, in the next decade and beyond. The practicality of replacing coal-fired plants that are already connected to an existing electric grid with SMRs is part of the future energy reality. In fact, Bill Gates’ TerraPower is about to do just this in the state of Wyoming.